- Home

- Anshuman Mohan

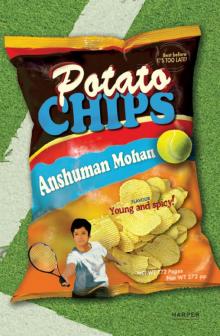

Potato Chips

Potato Chips Read online

for Shubho

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

One: Balancing the Equations

Two: Rewind and Play

Three: Opening a New Folder

Four: Lines and Angles

Five: Back to the Grind

Six: Manmade Disasters

Seven: Weight, Pressure and Us

Eight: Reading Between the Lines

Nine: No Competition, Please!

Ten: Summing Up the Problems

Eleven: Comprehend and Analyse

Twelve: Drawing Up Solutions

Thirteen: All’s Not Fair in Love and War

Fourteen: Greater Distances

Fifteen: Making Up Stories

Sixteen: Rights and Principles

Seventeen: Learning the Hard Way

Eighteen: The Last Bell

It’s Funky, it’s Fun, it’s YOU!

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

One

Balancing the Equations

‘Go! Get out of the class!’ yelled Fundoo to the three of us as we stood with our heads bent low, trying to conceal our giggles. ‘How dare you?’ she screamed, her eyes flaming. ‘Out of my sight, I say! Can’t you understand English?’

‘We can…’ ventured Rohan, a cheeky glint in his eye. Fundoo practically erupted with anger at his audacity, and the entire class burst into peals of laughter. I could feel them egging me on, asking me—just this once—to humiliate Fundoo and show her who was boss.

Suddenly, a sharp burst of pain shot up my right foot as a heavy shoe connected with it. I quickly turned towards the culprit—Ankit, the class prankster—and rapped him on his head with his own ruler. Fundoo whizzed around, shocked by my nerve, and commanded us out. ‘This is preposterous! I will complain to the Prefect!’ she threatened.

Several daring people muttered, ‘Please do.’

‘Ma’am, he was trying to fracture my foot,’ I offered by way of justification as I turned towards the door. As we sauntered out, we could hear Ankit explaining, expressing mock concern on my behalf and waving his hands wildly in all directions. He joined us outside within the minute.

‘Et too, Brute?’ he said to me. ‘Traitor!’ We all laughed because we knew that Ankit couldn’t care less if he was in the teachers’ bad books.

There was nothing unusual about this kind of thing. We mess up, teacher goes mad, threatens us, does nothing, chucks us out, calls us back in—it was all old hat for us. There was only one crucial problem—Father Prefect (the principal, to the less enlightened) actually catching us on one of his rounds. Man, that guy was intimidating! He would casually catch us by the collar, drag us into class and demand an explanation from the teacher. The teacher would panic, make something up and, in short, land us in a big bowl of hot soup.

We started scheming. We had to think of a way to avoid getting caught and to spend forty-five minutes.

‘She said get out, not stand out, remember?’ said Sameer. ‘So, for the next half-hour, we can do as we please!’ We were delighted with this careful breakdown and analysis.

‘Yeah, man! That makes sense.’ We congratulated him enthusiastically, thumping him on the back.

‘So, where to?’ I asked, as if looking for suggestions for a picnic location.

‘What about the library?’

‘No, no. Mercy, please! It’ll just remind me of my EVS project. Besides, the librarian will get suspicious,’ Rohan said.

‘Yeah, the library is out,’ I agreed.

‘Canteen?’ Sameer suggested.

I dismissed it. ‘No, some of the teachers will probably be there, having chai.’ I wondered what we could do. ‘Hey, I know,’ I said finally. ‘The loo! As long as we don’t faint because of the smell, it’ll be perfect.’

The others nodded and we sprinted off in the direction of the toilet, nodding curtly at the teachers whom we passed. Everyone would assume we had permission to be out of class.

When we arrived, the toilet was deserted. Only an eerie dripping sound from a leaky tap greeted us as we made ourselves at home. The white tiles, usually filthy, were gleaming today under the artificial light of a dozen bulbs. There was no water—or anything else, if you catch my drift—on the floor. The toilet would, naturally, get a whole lot messier after the lunch break. ‘Dont do yahan, do wahan’ and ‘Susunami’ were common enough phrases at Xavier’s.

Ankit promptly sat down on the freshly Phenyled floor and started off on the homework for the next period. He had managed to grab his exercise book from the classroom, and Sameer’s as well, and was now immersed in maps and continents. Let’s just say he was ‘comparing’ his answers with Sameer’s before writing them. I wonder sometimes if it wouldn’t be simpler all around to just photocopy the class topper’s homework and hand it in!

I had walked over to a cubicle to pee when Sameer asked, ‘So… what’s the latest?’

‘Don’t disturb me, you fool!’ Ankit yelled.

‘By the way, Aman,’ Rohan said, ignoring Ankit, ‘what shampoo do you use?’

‘Clinic All Clear.’

‘Does it make your hair silky?’

‘Of course. Here, see,’ I said, thrusting my head at him. ‘But who cares if it is silky, anyway?’

‘Oh! So you like it rough and fuzzy, do you?’ Rohan asked.

‘Actually, I prefer it gelled,’ I said, pulling up my fly.

His face very serious, Rohan said, ‘We’ve just talked about that hair… what about the hair on your head?’

‘Yuck!’ we all shouted, chasing Rohan around the toilet. I managed to landed a big kick on his rear and Sameer smacked him on the head.

Rohan always had a stock of dirty jokes up his sleeve. He never really said, ‘Okay, I’m going to tell you a joke.’ He just slipped it in, catching us unawares. He was a tall, fair-skinned chap, his intelligent brown eyes always bright with mischief. He always stood last in line at the assembly and created a lot of trouble for the teachers. The life and soul of the class, he was popular and very entertaining. Inspired by some footballer, he had taken to spiking his hair up in the centre of his head. He lived in Alipore and came to school in his glitzy, black Honda City. He was my best friend.

‘Rrrrrrrrrrring!’ the bell sounded. Freeing himself from our bear-lock, Rohan headed towards class. We followed, feeling like heroes because of the way we had flagrantly defied Fundoo by ‘misinterpreting’ her instructions. We were greeted with admiring smiles from our classmates and cold glares from the monitors when we entered.

Every week, Father Prefect chose ‘the most well-behaved class’ and announced it at the assembly. I thought it very stupid and childish, but our class teacher, Fair & Lovely, had other ideas. She had taken it on herself to make us the recipients of this ‘prestigious recognition’ at least once. Her efforts, so far, had been in vain since most of my classmates agreed with my point of view rather than hers. So this week, she had decided to appoint three monitors instead of the customary one—Sriniwasan (Mr Perfect) and his henchmen, Sohan (The Complaint Box) and Siddhu (The Fighter Cock). We called them Madras-Calcutta—Mad-Rascal-Kutta—because other, more descriptive swearwords were forbidden.

It suddenly occurred to me that word of this latest misdemeanour would definitely get to Fair & Lovely, thanks to Sohan and Siddhu. They were thoroughly incompetent monitors whose only skills were buttering up the teachers and telling tales. They carried the teachers’ books, helped them up the stairs, dusted the board after every period, and wiped their chairs and tables clean. The fact that they always needed wiping—I take credit for that. Madras-Calcutta always seemed to be saying, ‘Can I do this for you, ma’am?’ or ‘Please

let me do that, ma’am!’ or ‘X copied his homework from Y, ma’am’. Basically, what they really wanted to say was, ‘Can I lick your shoes clean, ma’am?’

Sriniwasan was the only capable monitor of the lot. He was a tall, dark, well-mannered chap. His uniform was always immaculate and oil practically dripped off his hair. The school debate team was incomplete without him. And the quiz team. And the chess team. And the cricket team. He impressed the teachers without really trying. I am sure he had been the monitor in every class from one to seven! The only subject I could best him in was Hindi. I always thanked my stars that our school did not have Tamil as a second language option, else he would have topped that too. He was the kind of boy every teacher and mother would fight over.

Within seconds, Fair & Lovely walked into class, her heels clicking loudly. She was a bit on the short side and most guys in class towered over her easily. She always wore saris or salwar suits, although it was Rohan’s greatest desire to see her in a miniskirt. And we all knew that her favourite colour was black—her nails were painted black! It had become a pastime for us to guess what she would be wearing that day. Her earrings always matched her clothes. Rohan would keep fantasizing that her jhumka would fall down and he would keep it for memory’s sake. Sameer would then say, ‘Sambhal, yaar, teri ma jaisi hai!’ to general applause and laughter.

As expected, Fair & Lovely knew about our misbehaviour. The four of us found ourselves standing up again. Déjà vu, I thought. But then she just commanded us to meet her in the staffroom during recess and started giving the class notes on the dissection of frogs. Our dissection was postponed till recess.

We waited for Fair & Lovely outside the staffroom sometime later, trembling with anxiety. F&L was a cool, composed and unbiased person, and we all respected her. And we were scared to death about being punished by her. As we stood waiting, the other students smirked at us, prophesying a dire fate for us. F&L finally emerged and frowned at us.

‘Meet me outside the canteen at three,’ she said and walked off without any kind of explanation.

‘What’s up with her?’ asked Rohan as we headed back towards the classroom.

‘I dunno!’ I said.

‘I know. She’s gonna cut us into little pieces and serve us up as human cutlets!’ Sameer said gleefully.

‘I prefer she does it in public, so there are witnesses to our murder!’ Rohan and I high-fived.

I had read in the newspaper just the other day about how a mad teacher had banged his student’s head on a wall, making him bleed almost to death. Was F&L really going to chop us up? I couldn’t help being a bit concerned.

We huddled together and opened our lunch boxes.

‘A toast!’ Ankit cried, raising his Pearlpet bottle in the air. ‘A toast to our lives! May our souls rest in peace after F&L is done with us! May we enjoy our last meals thoroughly!’

As usual, Rohan’s lunch was the best. Pizza, delicious pizza. That kid just lived on junk! I’d got bhindi sabzi. Sameer had bread pulao and Ankit had sandwiches.

‘Snack attack!’ we all cried and grabbed at each other’s food.

Ankit, Sameer, Rohan and I—we were the best of friends.

The three of us gathered at the canteen at three o’clock sharp.

The canteen was a ramshackle little place, located in the tiny space under the stairs. It sold wafers, soft drinks, sweets, puri bhaji, samosas and sandwiches. Although rumours suggested that the place deep-fried more flies than food, business was always booming. Grimy, filthy and black—the walls of the canteen could easily have been those of a rundown garage. In one corner sat two gas stoves with huge kadhais on them, oil bubbling away, keeping up the continuous stream of samosas and puris.

The four of us were wayward and naughty, but we never actually disobeyed orders and managed to stay near the top of the class. However, as Sameer pointed out, our biology grades would encounter a very sharp drop if we disobeyed this order. The teachers’ scolding was, in my mind, more like strongly worded advice, given in the hopes that we would correct ourselves. But this ‘runaway’ episode was one of our more serious escapades. Fair & Lovely was both lovely and fair, but she wasn’t exactly the most understanding teacher at Xavier’s. How many teachers do you know who can take a good joke, anyway? Even Sameer, who easily had the cleanest slate amongst us, was quaking in his shoes.

‘Dude, we’re dead! You don’t run out of Fundoo’s class and expect anyone to forgive you, let alone F&L. The two of them are chums!’ Sameer said.

I, for one, felt that we’d actually done the school a favour by doing something interesting for once. Otherwise, people who were ‘sentenced’ would usually chat outside the classroom instead of doing so inside. Plus, they would peep in every now and then and distract the kids in the class.

‘What’s taking her so long? I swear my carpool bhaiyya will murder me again after F&L is done with us,’ I complained.

Ankit just stood there, his eyes closed as if in meditation. Suddenly, he opened them and let out a loud battle cry, making weird signs in the air. He was putting ‘potion ingredients’ into a ‘flaming cauldron’—kaala jaadoo to keep F&L away. ‘I hope she doesn’t come,’ he chanted over and over again, like some sort of frantic mantra.

At that very moment, F&L appeared around the corner. We snapped to attention, backs straight, arms by our sides, awaiting our moment of truth. I rehearsed my apology speech over and over again in my mind. We had all agreed to just accept whatever she charged us with, say, ‘Guilty of all charges,’ and scram.

F&L, however, had other plans. She took her time coming to us, making us more nervous by the second. Finally, she reached us and casually looked around the canteen, as if hoping that somebody would join us.

‘Sit down,’ she said.

We obeyed without question.

‘Santosh!’ she called out in the general direction of the stoves.

I caught Rohan’s eye and nodded meaningfully. Had she finally gone mad?

After a while, a small figure dressed in a grey shirt came into view. I recognized the boy as the assistant of the owner of the canteen, Punditjee. His shirt was stained with dirt, his hair was ruffled and his face was red from the heat under the stairs. He had dark circles under his eyes and his face was lined with tiredness. His eyes, however, were a different story. Liquid brown and intelligent, they twinkled as he sized us up.

‘Santosh lives and studies in Ramkrishna Mission, Narendrapur,’ F&L said. ‘He tops his class and his school supports him in any way they can. His parents live in Kolkata, while he boards at school. During his holidays, and every now and then, he comes over to Xavier’s to lend a hand at the canteen. He applied for admission to Xavier’s last year. He even got through the gruelling qualification process and was chosen. But his parents refused to put him in because they couldn’t even come close to paying the school fees. Father Prefect offered them a huge fee concession, but their means are meagre and they refused. Had Santosh got admitted, he would have been one class junior to you.’ F&L paused to breathe—she had been speaking in a great rush of emotion. ‘Do you realize what I mean by telling you this? You are privileged. Many are not. This boy is gifted, but his dreams will probably be unrealized forever, while you lot play your silly pranks all day.’ She stood up. ‘Waste time or make the most of it,’ she said and walked out.

I was stunned by F&L’s revelations about the boy we were used to bossing around—I had once ordered him to go and buy me a snack from across the street because we were not permitted to leave the school premises. But F&L had taken the time to find out more about the boy the students basically treated like dirt. I suddenly started respecting her ten times more than before.

‘Chal, yaar!’ Rohan said. ‘We’re getting late.’

We walked out towards our grumbling carpool dadas.

I left school with a heavy heart. I promised myself that I would be kind to Santosh from now on. I would even buy him a new T-shirt with my pocket money.

&n

bsp; I mumbled some lame excuse for my unpunctuality to my carpool driver and stepped into the cramped car. The rest of the gang dispersed towards their respective modes of conveyance. As the Sumo rattled along through the noisy streets, sounding more like a tractor than a car, I slowly inspected my surroundings. We were passing through Park Street, the place where all things hip and happening happened. Although our loser government had changed its name to Mother Teresa Sarani, no one called it by that name. Park Street just fit. This place had life. It had seen the birth and slow death of live bands and fine-dining restaurants. It was the place of pubs, bars, latest fashions, the place where the whole city turned up every year to look at the Christmas decorations. Although I passed this road every school day, I had never really bothered to look around and think about it all. Today, everything seemed more meaningful, and I realized how lucky I was that I could take all of this for granted without worrying about having the time or money to hang out here with my friends.

When I got home, however, my mood improved. I bullied my sister, ate, did my homework, bullied my sister some more, went to play tennis, came back. In the evening, I made three phonecalls.

Hyperactive Rohan was apparently asleep.

Ankit had run out of gossip and spoke in monosyllables.

Sameer just nagged me for being so indisciplined.

The next day, we all went to school feeling very pleased with ourselves. Although the monitors gave the four of us ‘last warnings’ if we so much as sneezed too loudly, we weren’t planning to do anything that would give them a chance to complain to the teachers. The only thing that was unusual was that Fair & Lovely was not wearing earrings that matched her dress.

‘Her dress is blue and the earrings are pink!’ Rohan declared joyously. I pitied him. The guy had clearly never heard the word ‘contrast’.

The day was mostly uneventful. It had been announced that our class would have to conduct the assembly next week. Now, assemblies at Xavier’s were not exactly ‘normal’. They took place in the massive front field, with all the classes arranged in rows and columns, facing a podium that acted as the stage. The assemblies were very elaborate, with a theme for each class to act out, and a special panel of teachers was in charge of the smooth execution of the show. The more peculiar the assemblies were, the better. They often included news reports, dances, skits, prayers and songs and went on and on for almost half an hour.

Potato Chips

Potato Chips